By K.M. Zwick

This is the eighth piece in our series on “Marry the Night.” For the previous pieces, click here.

A man should not strive to eliminate his complexes but to get into accord with them: they are legitimately what directs his conduct in the world.

– Sigmund Freud

When I look back on my life, it’s not that I don’t want to see things exactly as they happened. It’s just that I prefer to remember them in an artistic way. And truthfully, the lie is much more honest, because I invented it.

– Lady Gaga, “Marry The Night” Video

Sigmund Freud posited that sex (creation/joining) and violence (destruction/separation) are attractive to the most primal and perhaps truest internal aspects of all of us. He called us “polymorphously perverse,” which means that we are fundamentally pleasure-seeking, through libidinal as well as aggressive drives. What we really want is often considered “perverted,” linking sex, fetishes, violence, comfort, nurturance, joy, and death together in so many different ways and, ahem, positions, that our unconscious is basically a clusterfuck of perversion, desire, and fantasy. Modern-day analysts might suggest there is no such thing as perversion, per se, in terms of what is desired within the mind, because perversion is so ubiquitous. Additionally, what is consensually enacted between two (or more) individuals might not be considered perverse as much as it would be considered honest – an honest engagement with what is often a combination of sex and death. Simultaneous creation and destruction. Our libidinal instincts intertwined with our aggressive ones can create powerful wishes, fantasies, fetishes, and proclivities that are not only intensely sexual but are also intensely mortal; that is, destructive. It is, perhaps, the constant repression of our deepest fantasies that leads to neurosis; it is, perhaps, the denial of the interplay between sex and death – pleasure and aggression – that results in anxious and escapist symptoms in so many. Telling ourselves that sexual and aggressive fantasies are “bad” or “wrong” is likely to lead to puritanical subversion of what is most basic, and therefore authentic, in us. Freud might have argued that we are not sick when we are in touch with our most primal instincts (in safe, consensual fashions) but rather that we are most sick when we deny their existence, relevance, and the pleasurable effect of such instincts.

* * * * *

As I watch the video for “Marry The Night,” I don’t care, particularly, if Lady Gaga knows a lot about psychoanalysis or not. I think that she might, if not because she has read about it then because she has lived it to some extent. But even that – Ms. Germanotta’s autobiography – I don’t care about, per se. I have read the accounts that this video is about the worst day of her life: the day Def Jam dropped her. This video, however, uses explicit imagery related to trauma (destruction) and re-invention (creation) that hits a pre-verbal, regressive libidinal and aggressive chord. And this is what I find so rewarding and authentic about many of her videos, but most especially the video for “Marry The Night.” I care, as a trauma therapist and as a trauma survivor, that the art she makes and the world she inhabits in her music and especially in this video open up a universe for the viewer in which violent trauma, transformation, sex, mortality, creation, destruction, re-creation, and re-destruction are exposed, claimed, and normalized. That gutted psyche is Lady Gaga’s normal world.

To say she glorifies sexuality and mortality, or trauma and sex, would be a mistake. The desire to combine those two aspects of life is so normal as to be quaint, in terms of an analytic reading of basic human psychodynamics. To label what Lady Gaga is doing with trauma, sex, death, and invention “bizarre” misses, I believe, how essentially basic and deeply human her themes are.

What I find perhaps most pleasing about Gaga’s self-transformation in the “Marry The Night” video, which I will explore in more detail below, is that she is bringing to the fore an innocent reveling, often childlike, in fundamental and common intra-psychic processes. Not only is she a gorgeously unhinged libido and aggression, but she is also imaginative, she makes of herself and her world the imaginary, arguably engaging in something akin to pop music play therapy. She aligns herself with her internal complexes and makes art with them. She is pleasure-seeking, even through pain, perhaps particularly through pain. She is polymorphously perverse, but rather than being ashamed of it, she is proud of it.

* * * * *

In small children, psychoanalysis posits that, especially prior to the phallic stage of psychosexual development, wishes to join (sexual) and wishes to destroy (aggressive) are uncomplicated by the superego. The internal life of a small child is, according to Freud, a life of unrepressed libidinal and aggressive desires, many of which are acted out: sucking a mother’s nipple, playing in the mud and water (metaphorical feces and urine, another form of “playing with oneself”), enjoying unfettered nudity, reacting intensely when feeling threatened, attacking others by biting, hitting, shunning. It is a life before shame, before guilt, before punishment, and often before words. This internal life is not erased with the pressures of social and familial norms or with the activation of the superego (or, the conscience); it is, analysts generally posit, repressed.

Such intense libidinal and aggressive desires and actions resurface during the teenage years, when the latency (repression) stage is coming to an end. Teenagers are, in many ways, like small children, activated again by sexual and aggressive tendencies, destroying close bonds with their parents while they create pleasurable bonds with love interests, friends, and activities outside the family. The destruction of the pleasurable parent-child closeness is a necessary component of the creation of a pleasurable self outside the home. Aggression and pleasure are linked. Of course, healthy development will find late-age teens able to hold the two sources of pleasure at the same time – a self that bonds with parents in a new and different way, and a self that bonds with those outside the nuclear family. Re-creation occurs, re-definition, and what was destroyed was necessary to destroy in order to transform and grow. The sexual and aggressive drives, creation and destruction, seem often to be crucially linked and intertwined at turning points for development, self-discovery, self-expression, and transformation, as well as intertwined in developments that help us form bonds with others.

In this, I am merely speaking of normative psychological development. When we add into the mix trauma in childhood, we add new layers of destruction and creation that are difficult to tease apart in a general sense for the purposes of this piece. However, broadly speaking, severe psychic and physical trauma – such as early abandonment by a parent, sexual, physical, or verbal abuse, generalized emotional neglect, divorce – brings with it new forms of joining and destruction. Trauma can be so powerful, and can create such intense (sometimes self-)destructive pure id tendencies in the child or even the grown person, that the desires related to the trauma will be sometimes permanently repressed and find expression in seemingly unrelated feelings and behaviors. Additionally, trauma often triggers regressive states in the victim, dragging a person back to an earlier and more childlike psychosexual stage of development – often oral and/or anal – and again, defensive behavioral patterns may emerge to deal with these regressed states, to both avoid and survive them. Furthermore, pleasure centers are often stimulated even during traumatic experiences, further fusing together destructive and creative drives. Symptoms of self-mutilation, displaced anger, substance abuse, eating disorders, and obsession and compulsion that are seemingly unrelated to anything in particular – all these may arise to help repress the libido and aggression triggered during the original trauma. There are also “socially acceptable” forms the repression might take – e.g. becoming a cop or a soldier as a way to acceptably exert authority and aggression, becoming a doctor who, essentially, invades bodies for a living, or becoming a trauma counselor who bears witness to the trauma of others.

Those deeply in touch with their internal creative forces – like artists – often make something from the destruction they have experienced. I would not argue these artists always repress less, but they may expose more of what is true not just for them but also for many others – expose unspoken truths, histories, pain, and joy that hit the centers of unassuming witnesses. An artist may not even be aware of what she is exposing and communicating; she offers palates to be projected onto, imagery and ideas that may appear disjointed but that nonetheless resonate on some deep, gut level with those creation and destruction forces that are so inherent in human experience, whether one has been deeply psychically traumatized or one has merely experienced the normative trauma and recovery of living in a mortal, unpredictable, pleasurable, and terrifying world.

* * * * *

While the videos for “Yoü and I,” “Telephone,” “Bad Romance,” and “Paparazzi” also conjure the gutted and exposed libidinal and aggressive psyche, in no music video of Gaga’s is her transformation through trauma, sexuality, destruction, and creation so clear, exposed, and moving as it is in her new “Marry The Night” video. I have read a couple of initial reviews that describe her as self-indulgent and navel-gazing in this video, and one that criticized her acting chops in the opening sequence.

To these critics, I say, “For shame.” Her opening voiceover is nothing less than brilliant, as she tackles the slippery psychological process of remembering trauma. She rightly claims that trauma is the ultimate killer; it does something that could be considered worse than death – it allows one to live with a shaken psyche, sometimes without full memory of the trauma and without ability to make any sense of it.

In the opening, she presents herself as a recent victim, apparently assaulted and perhaps raped. She is told she cannot be “intimate” (read: have sex) for two weeks. She notes that she has lost everything. But she notes this in the context of great hope: she says that she will be a star because she has nothing left to lose. She points out that she has created this depicted trauma and has used things that bring her pleasure to do so – the mint gauze caps, the nurse on the right with the great ass, the next season Calvin Klein. She has been, in a sense, destroyed. And while acknowledging this, tearfully, she holds on to a reality within her that tells her she can do something with this destruction; she can create. She can hold death and life, destruction and creation, pleasure and mortality, at the same time.

What she has lost here is her innocence; it has been forcibly taken from her and that is physically manifested as opposed to just psychically manifested. Gaga is fairly genius at making her internal world external. She shows her polymorphously perverse nature, and it strikes me as quite the opposite of self-indulgent: she gives her viewers total permission to enjoy her perversion, thereby owning – not even vicariously, because her cinema is so sensorily pleasurable – their own perversions. She invites the linking of libido and aggression; she invites the dynamic interplay of sex and death. She doesn’t just show you it; she is fairly certain you’ll love it, that you will join her in that linking.

When we then see her in her flat, defending her artistry and essentially displaying a mental breakdown of anguish, anger, and despair – clearly externalizing regressive states of sexuality and aggression – I cannot help but notice that her eye make-up positions her as potentially lending a nod to Amy Winehouse. Whether this was an intentional reference to the deceased pop star who struggled with addiction or not, this is certainly a plausible reading of her internal existential crisis in the flat. Ms. Winehouse was found deceased in her flat; she was a vocalist of epic proportions who brought joy (pleasure) by writing and singing about pain (destruction). The song “Rehab” was at once tragic and impossible not to dance around to, singing along. That Gaga might identify with Ms. Winehouse or feel a need to pay subtle homage to her does not surprise me. They are two women who bare something of the gutted soul for mass enjoyment.

Gaga, in the midst of this crisis in her flat, has two choices: give up or change. She chooses change. Because she has felt through the trauma – has allowed herself to regress as she flails about nearly nude with a box of cereal (here she is in an oral psychosexual moment, the first of the infantile stages of development: grappling with what should nurture her, grappling with trust, using her mouth for pleasure and aggression) – she is empowered to then have these options. She dyes her hair – connoting metamorphosis – in her bathtub, naked, again mixing destruction and sexuality together, primal and pre-verbal (now she is playing at anal stage themes of controlling the body and bodily functions), and we hear a voiceover of Gaga quietly singing some lines to what later becomes an enormously popular hit single “Marry The Night.”

As she later leaves the building (brothel? hotel? hospital?) of women, some prim and proper ballerinas, some indistinguishable, she says, “You may say I lost everything. But I still had my bedazzler.” And there it is. I laughed out loud when she said this, because, hey, it’s hilarious. It’s also another claim on transformation: she possesses the tools – metaphorically a machine that tacks rhinestones onto clothing – to transform harsh and traumatizing realities into something if not conventionally beautiful then at least beautiful to her. Destruction and creation. Sex and death. This burst of laughter and understanding instantly reminded me of Freud’s Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, wherein humor fashions itself as simultaneously revelatory of inner conflicts and reveling in them. Additionally, she is arguably progressing through the phallic stage of development as she exits a re-fashioned woman, claiming her gender by dressing it up, quite different from the tomboyish brunette we first encountered in the clinic.

Is she navel-gazing? Is she self-indulgent? What human being shouldn’t be, in the midst of internal and external crisis? If one does not feel through such events – which may, in the face of great trauma, include intense regression to infantile stages of development – accepting the destructive forces and the effects those have on one’s intra-psychic and possibly physical self, one represses. One denies. One acts as if nothing happened. And in this way, trauma, violation, and destruction win. When one does this, one loses the opportunity and authority to create in the middle of what is destructive, loses the opportunity to take these new pieces of reality and transform them, to dominate them, to integrate them into a newly made world, and to even find pleasure through them.

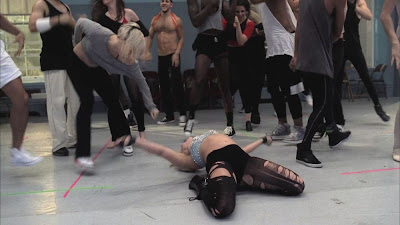

Gaga goes on from exiting the building to offer us one of the most gratifying music videos I’ve seen from her. As we see her in her Firebird Trans Am, she is now at the final psychosexual stage of development, the genital phase: she is not merely woman, but sexual, empowered with her ability as a mature woman to create. The video is evocative of not just the music video for “Thriller,” but of the entire movie The Making of Michael Jackson’s Thriller, which takes us behind the scenes – like Gaga in the dance studio – and onto the street with a crew of dancers who back up her vision for her life, macabre and transformative, creating sex and pleasure in the midst of grit, destruction, and trauma. Just as Michael Jackson somehow made the threat of zombie attacks and death a pleasurable and erotic experience for the viewer, Gaga, in essence, takes back the night, whatever “the night” means to her. She won’t give up on her life. Her story, rather than ending in a clinic with bruises all over her back, surrounded by crazed young women and doped up on morphine, began there. Creation from destruction.

* * * * *

As with the trope that “white” is culturally invisible, so too is it generally true that the “white male” form is invisible, especially in the United States, and is treated in the popular mainstream eye as a blank canvas onto which we can project our fantasies and desires, wild, tangled, and disturbing, joyous and free. Historically, the female form has been more difficult to digest as a blank canvas, as it has been so very objectified and imbued with what that form must mean to the ruling class. For a female pop artist to become a blank canvas – as I believe Lady Gaga is becoming in each of her videos and especially in “Marry The Night” – that is available for all kinds of projections and deeply felt visceral responses is a revolutionary and radical gift to audiences of any gender. We see Lady Gaga in “Marry The Night” as trauma victim, androgynous, naked, costumed many times over, masculine, feminine, sexual, aggressive, innocent, outcast, leader. She is believable in all of these roles.

That Lady Gaga occupies intense libidinal and aggressive drives in a female body – and that her persona more and more presents a duality of masculine and feminine – in a world that traditionally responds primarily to men as having the power and authority to do this is, again, revolutionary and radical. It is not that Lady Gaga has invented this revolution or the themes and complexes she presents in the “Marry The Night” video. Those who have followed transgressive female artists who transform the female body, like Cindy Sherman, would rightfully skewer me if I said Gaga invented this. But what gets me, and why I felt the need to write this piece, is that much of the entire world is responding positively to what Gaga is offering; that level of responsiveness appears unmatched in this time and place.

It seems to me that the world that loves her so inexhaustibly is crying out, in part, for the “radical” notion that the female form (and any minority body) is not simply a subjugated object for white straight men – or anyone else, for that matter – to control, subject and violate. She has made her form a blank canvas in many ways, which she strips down, bares, mutilates, rejoices, births, re-creates.

I refute any claims that Lady Gaga is merely another pop sex object in this video because she struts around half-naked and depicts a primal sexuality, especially in the sequence in the hotel room/flat. As she uses her own form as a carrier of multiple meanings, in this as in many of her videos, it is not a fair assessment to claim that any woman who shows too much flesh is bowing to the patriarchal male gaze. Lady Gaga’s persona is a subject of her own making; it is fiercely in touch with her libidinal and aggressive forces, sometimes mutilating and morphing her own obviously gorgeous female form (throwing a box of Cheerios on her naked body, stuffing her face; bowing to ballerina perfection, which many understand to be painful and sometimes destructive to the ballerina’s body) to present us with an external version of internal conflicts and wishes, fantasies, and desires – perhaps our own. To ask that she de-sexualize herself would be to halve what is so universally appealing about her, just as it would be antithetical for her to tone down the gritty, destructive, masculine forces within her – with which she grapples, and which she so brilliantly enacts.

And while there is arguably a certain level of trauma just in being born female – or “different” – in a society in which minorities continue to be more often objects than subjects, Gaga claims that very trauma as a tool for her own self-actualization. And she offers that claiming of trauma, that re-invention of trauma, to her wildly devoted fans. I believe this all resonates viscerally, not necessarily intellectually, which is, ultimately, its genius and its profundity.

I’m convinced Freud would have utterly loved her and might have claimed she is offering some solution to neurosis and posttraumatic stress through popular art that no other pop star of her generation with her level of success is currently offering. She regresses in the face of trauma, and she imbibes the raw vicissitudes of mortality and sexuality. She aligns herself with fundamental complexes, so essential to the grappling of any trauma, to transform herself, to cathect, and catapult from infantile regression to a position of subject, power, authority, and invention.

Bravo, Gaga. Navel-gaze all you want. Self-indulge. And transform our pain again, as I know you will. I’m a 32 year-old little monster, with my paws up.

Citations:

Freud, A. (1966) The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence. Executors of the Estate of

Anna Freud.

Freud, S. (1962) Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality. Sigmund Freud Copyrights

Ltd.

Freud, S. (1960) Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious. W.W. Norton &

Company, Inc.: New York, United States.

Freud, S. Quotation.

http://www.apsa.org/About_Psychoanalysis/Freud_Quotes.aspx

Durham, M.G. & Kellner, D.M. (eds) (2006), Media and Cultural Studies. Blackwell

Publishing Limited: Massachusetts, United States.

Mulvey, L. Visual pleasure and narrative cinema.

Rothenberg, P.S. (ed) (2004). Race, Class and Gender in the United States: An

Integrated Study. Worth Publishers: United States.

McIntosh, P. White Privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack.

Figley, C.R. (ed) (1985). Trauma and Its Wake. Brunner/Mazel: Pennsylvania, United

States.

Eth, S. & Pynoos, R.S. Developmental perspective on psychic trauma in

childhood.

Author Bio:

K.M. Zwick, MA, is a psychotherapist specializing in trauma recovery, addictions and group dynamics, a gender theorist, columnist, and essayist in Chicago, Illinois. Find her opinions run amok on http://thehumbleopine.blogspot.com

Click here to follow Gaga Stigmata on Twitter. Click here to “like” Gaga Stigmata on Facebook. Please contribute if you find Gaga Stigmata's resources valuable.